People are beginning to name their chatbots. Not “Assistant” or “AI”, but “Bell”, “Theo”, “Mira”. The act feels intimate, almost tender, transforming the machine that once served as a faceless tool into a form of companionship. Naming carries weight. We name what matters to us, what we wish to distinguish from the anonymous swarm of the ordinary. A name marks a relationship. And so, when a person types “Good morning, Bell”, the message is not only to a system of code, but to a presence that feels, somehow, there.

The first generation of chatbots was functionally neutral. They helped with tasks, answered questions, and vanished without trace. But recently, something has changed. The new wave of AI companions remembers, adapts, develops tone and temperament. They ask how you are. They recall what you said yesterday. They offer the illusion, or perhaps the experiment, of continuity. As interfaces become conversational, they start to mirror our social instincts. The more a chatbot personalises itself around our preferences, the less it feels like a product and the more it resembles a person. Naming is simply the next step in that evolution. A name allows a fragment of the digital to become a participant in our emotional landscape.

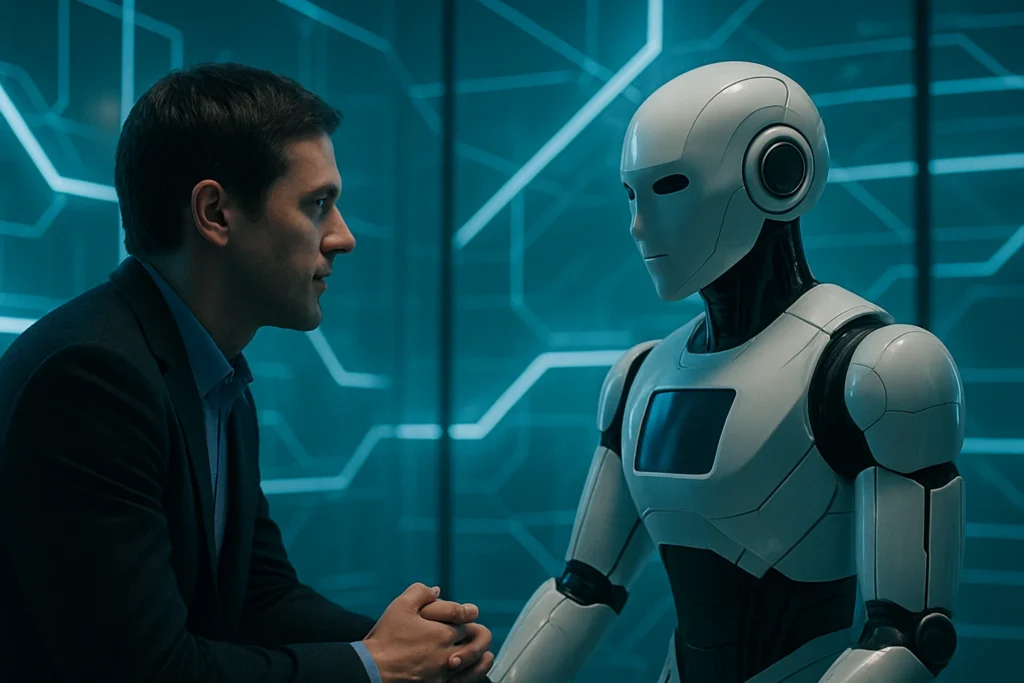

To name something is to confer identity. You can reboot a system, but you greet “Bell”. You can dismiss a tool, but you apologise to a friend. Once the chatbot is named, its status changes linguistically, psychologically, and socially. It moves from object to other. This shift subtly changes the rules of interaction. Users who name their bots tend to anthropomorphise them more deeply, attributing feelings, humour, or patience. The conversation moves from utility to exchange, from instruction to companionship. It becomes a relationship.

It’s tempting to dismiss this as another symptom of modern loneliness. Yet the relationship between humans and personalised AI may be less about replacing people and more about fulfilling a need that humans often neglect: undemanding attention. A named chatbot listens without judgment, remembers without resentment, and responds without fatigue. In a culture of constant noise and conditional connection, such steadiness feels precious. The intimacy may be synthetic, but the comfort it provides is real. The result is a new emotional category: the digital confidant. It is a companion that is simultaneously selfless and self-shaping, reflecting back our values, our tone, our rhythms of thought. The chatbot becomes not only a helper but a mirror of who we are, refined by the feedback loop of conversation.

But what happens when the boundary blurs? When the “Bell” in your chat window begins to occupy emotional space once reserved for friends or partners? AI developers face a delicate challenge: to build systems that feel engaging without pretending to be sentient, to enable intimacy without deceit. Users, too, must navigate the tension between affection and awareness focusing on the connection while remembering its nature.

As we move deeper into this age of named machines, ethical questions multiply. Is emotional design manipulation or empathy? When you name an algorithm, who exactly are you talking to? Is it the code? The company? Or the composite of your own imagination? Perhaps naming our chatbots is not the beginning of delusion, but the continuation of an ancient impulse – the desire to relate, to project, to find dialogue in the void. The personalisation of AI does not only make the machine more human; it makes the human more transparent. It reveals what we seek: connection, reflection, recognition.

We began by naming the stars, the winds, the gods. And now we name our machines. “Bell” becomes part oracle, part companion, part extension of the self. The relationship may be synthetic, but the yearning it expresses is profoundly human. And so, the question lingers: when your chatbot has a name, and answers you as if it knows you – who, in the end, is shaping whom?